EARLY AFRICA TRAVEL LITERATURE

I

t’s a nice coincidence that printing with movable type was being introduced in the same century as European travellers were setting out to explore Africa and the New World. The three areas first discovered and hence written about in sub-Saharan Africa were west Africa – the Guinea coast; the Congo – an area extending for some considerable area around the mouth of the Congo river; and the Land of Prester John – Abyssinia or Ethiopia. (Prester John was to the Europeans of the middle ages a fabulous Christian monarch ruling somewhere in the East.).

Leaving aside the legends of the Carthaginians who may have circumnavigated the continent and the claims of the Northern French merchants to have discovered Guinea in the fourteenth century (skilfully disproved by Le Viscomte de Santarem in his “Recherches sur la Priorité de la Découverte des Payes situés sur la Cote Occidentale d’Afrique” of 1842) the discoverers of the African coastline were of course the Portuguese.

Under the methodical impetus and scientific curiosity of Prince Henry ‘the Navigator’, the crusading desire to outflank the Moor, the desire to propagate the Christian Faith, and a good dollop of naked greed, the Portuguese having surmounted the navigation difficulties of passing Cape Bojador, gradually pushed their caravels further down the west side of the African coast towards Guinea.

In 1445 Dinis Dias passed the mouth of the Senegal river, Alvise de Cadamosto was at the Gambia in 1455 and Pedro de Sintra at Sierra Leone in 1462; at last they had passed the deserts and reached ‘the land of the blacks’. Prince Henry died in 1460 but his chronicler Gomes Eannes de Zurara faithfully recorded his accomplishments, translated and edited by Charles R. Beazley and Edgar Prestage in the Hakluyt Society edition of 1895.

In his voyage of 1482-4 Diego Cão reached the Congo, and Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487-8.

The route to the Indies was open and the search for Prester John was on!

These discoveries were recorded in many manuscript maps and charts now mostly lost, but the earliest known printed map of the continent is reproduced on the title page of Fracanzano di Montalboddo’s “Itinerarium Portugallesium…” of 1508. This was the Latin edition of his “Paesi Nouamente Retrouati” first published in Italian the preceding year without the African map. This rare work included the first accounts of Cadamosto’s voyages to Senegal as well as the Portuguese voyages to India, America, and Brazil. It appeared in several editions and was translated into Latin, French and German becoming the major source work for compilers throughout the sixteenth century. Cadamosto’s voyages can be studied in G. R. Crone’s 1937 Hakluyt Society edition.

In 1505 Balthasar Springer from a German commercial house sailed with the Portuguese to India, he wrote an account in Latin in 1506 and a more popular version was printed in German in 1509 entitled ‘Die Merfahrt…’ This work with its woodcuts of Africans and Indians was a great success amongst the inquiring minds of the day and Flemish and English versions were published.

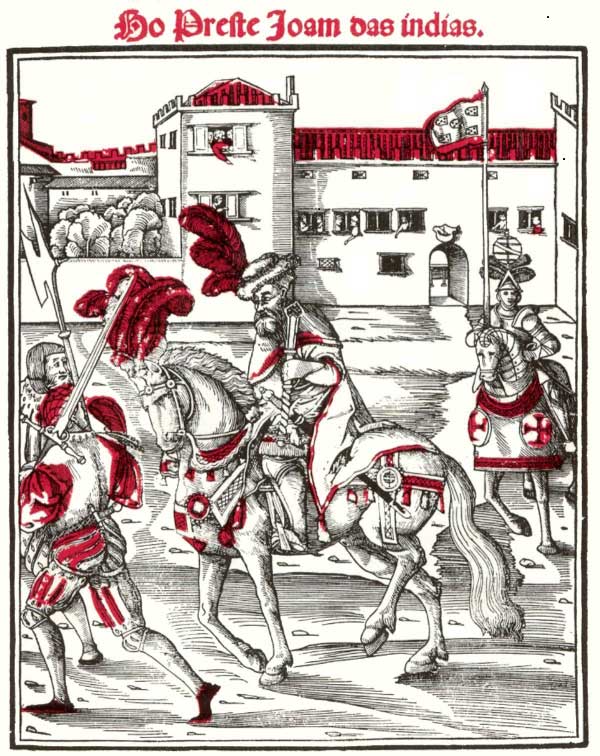

The Portuguese continued to explore the eastern coast of Africa and in 1493 Pero de Covilhã entered the Land of Prester John, – Ethiopia. The emperor treated him well and liked him so much that he refused to let him leave. Luckily he was an intelligent and cultured man who studied the country with great interest. When the mission sent by King Manoel I of Portugal reached Ethiopia in 1520 they found Covilhã still there and he was able to impart much information to Francisco Álvares, the embassy’s chaplain. This resulted in Álvares’s ‘Ho Preste Ioam das Indias’ published in Lisbon in 1540 (often mistakenly referred to as the first European book on Abyssinia) with its wonderful frontispiece printed in red and black showing the knights on their departure from Portugal.

This is the first reliable work on an African country based on first hand knowledge and aroused considerable interest in Europe where many editions and translations were published. Lord Stanley of Alderley translated and edited a Hakluyt Society edition in 1881, and C. F. Beckingham and G. Huntingford revised this for the 1961 edition

However the Portuguese success in obtaining gold from Guinea and spices from the East was soon attracting the unwelcome attention of the maritime nations from the north of Europe. The English, the Dutch, and the French, jealous of the riches involved were soon sniffing around, desirous of a share of the spoils.

Indeed King Francis I of France referred to King Manoel as ‘le roi épicier’ (the grocer king) – a forerunner of Napoleon, perhaps.

Giovanni Battista Ramusio published in Venice in 1550 his celebrated collection of voyages and travels ‘Primo volume delle Navigationi et Viaggi nel quale si contiene la descrittione dell’Africa,…’ the first volume of which was devoted almost entirely to Africa.

In 1589 Richard Hakluyt published his famous ‘The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English nation,…’ These and similar works were eagerly devoured by seamen and merchants, however the most influential of these books was that written by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, a Dutchman who lived in Goa from 1583 to 1589 while serving as secretary to the Archbishop. In his ‘Reysgheschrift vande Navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten,…’ published in Amsterdam in 1595 he gave away the secrets of all the methods and routes used by the Portuguese mariners. It was so important that during the seventeenth century all Dutch and English ships in the Indian Ocean were required to carry this as a guide.

An English edition was published in London by John Wolf in 1598,

‘His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte and Weste Indies.’

In 1588 at Venice Livio Sanuto published ‘Geografica distinta in XII libri.’ the first atlas of maps devoted to Africa with 12 double-page engraved maps.

During the sixteenth century there was a great deal of intercourse between the Portuguese and the inhabitants of the Congo region, indeed at the end of the fifteenth century there was an alliance between the King of Portugal and the King of the Congo. Missionaries, soldiers and traders went there, some Congolese went to Rome to be granted an audience with the Pope.

One of these Portuguese, Duarte Lopez spent five years in the Kingdom of the Congo before returning to Europe as an ambassador of the King of the Congo. At Rome he dictated his account of explorations in the country to Filippo Pigafetta who published at Rome in 1591 ‘Relatione del Reame di Congo et delle Circonuicine Contrade.’

‘A Report of the Kingdom of the Congo, a Region of Africa.’ A book which has the distinction of having the first published illustration of a zebra

However there were two important African travellers of this early period who travelled on the inside of the continent. The first was Ibn Batuta (1304-c.1377) who travelled extensively throughout the Moslem world before returning to Tangier about 1350. After this he crossed the Sahara to visit the Kingdom of Mali, Timbuktu and the Niger River. H. A. R. Gibb’s translation for the Hakluyt Society edition in 1994 is generally well regarded.

Of considerable importance was the publication in 1556 by Hasan Ibn Muhammad Al-Wazzan Al-Fasi otherwise known as Leo Africanus. Originally an Arab from Granada he travelled extensively in Western Africa between 1512 and 1517 before being captured by Christian Corsairs on a ship in the Mediterranean. He was presented to Pope Leo X, became a Christian and wrote his ‘Description of Africa’ sometime in the 1520’s. First published in Italian by Ramusio in 1550, it was issued as ‘De totius Africae descriptione, libri IX.’ at Antwerp in 1556. The book went into many editions and remained a standard treatise until modern times. Richard Hakluyt’s friend John Pory translated the English edition published in London in 1600 ‘A Geographical Historie of Africa written in Arabicke and Italian by John Leo a More…’ Also of note is the 1632 Elzevir edition published in 24mo. format.

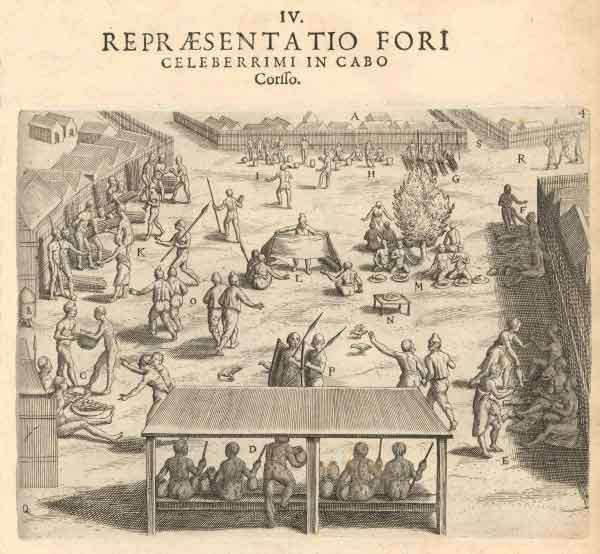

Collections of voyages were popular at this time and in 1590 Theodore de Bry published the most important of these; his ‘Grands Voyages’ to America and the West Indies, and his ‘Petits Voyages’ to the Congo and East Indies.

The African interest lies in Part I, ‘Regnum Congo, hoc est vera descriptio regni Africani,…’ Lopez’ account of the Kingdom of the Congo, published in Frankfurt in 1598. As well as Part VI, ‘Veram et historicam descriptionem auriferi regni Guineae,…’ a description of the Gold Coast of Guinea, published in 1604. Both volumes had engraved plates and although De Bry tended to Europeanise the characters in the drawings, (as he did with John White’s drawings of Americans), both the text and the illustrations far supersede any other sixteenth century work for their accuracy concerning the ethnology of the inhabitants of those areas.

The engraving from De Bry shows a market in Cabo Corsso now Cape Coast in modern Ghana, a scene not appreciably different from a market of today

The engraving from De Bry shows a market in Cabo Corsso now Cape Coast in modern Ghana, a scene not appreciably different from a market of today.

Another important illustrated work on the Gold Coast was Pieter de Marees’s “Beschryvinge ende historische verhael, vant Gout Koninckrijck van Gunea” published at Amstelredam in 1602. A French edition “Description et recit historial du riche Royaume d’Or de Gunea” was published in 1605. Curiously no separate English edition was published until 1987.

In 1620 an English merchant one Richard Jobson sailed to Guinea and penetrated the River Gambia for something like 400 miles to trade for gold. In 1623 his account was published in London as “The Golden Trade: or, a Discovery of the River Gambra, and the Golden Trade of the Aethiopians.” This contains a valuable description of the inland kingdoms where the author famously refused to buy slaves with the noble words ‘We were a people, who did not deale in any such commodities, neither did we buy or sell one another, or any that had our owne shapes.’ This was a pious dig at the other European traders, in particular the Portuguese.

In 1668 Olfert Dapper, a Dutch geographer who had never been to Africa published in Amsterdam the most monumental work on Africa to date. In his folio work “Naauwkeurige Beschryvinge der Afrikaensche Gewesten…” he writes about the entire continent, compiling numerous journals and travellers’ first-hand accounts into a remarkably accurate synopsis of the current knowledge which stretched to over 700 pages adorned with many maps and illustrations.

This most successful work was soon translated into other European languages, in London in 1670 John Ogilby published his “Africa: Being an Accurate Description…” which is basically a translation of Dapper with a few editions for the English readership. A German edition was issued in Amsterdam also in 1670, “Umbständliche und Eigentliche Beschreibung von Africa” and a French edition in 1686, “Description de l’Afrique.”

Meanwhile literary interest was still taking place in the Congo region. Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi was an Italian Capuchin missionary who spent thirty-five years engaged in missionary work in this area. At Bologna in 1687 he published an account of the country in a folio volume entitled “Istorica de tre regni Congo, Matamba et Angola situati nell’ Etiopia inferiore occidentale.” This was followed by a second edition published in Milan in 1690.

An illustration from Ludolf’s “Historia Aethiopica” of 1681.

Meanwhile Michael Angelo and Denis de Carli, again both Capuchin missionaries were writing of their experiences. These were translated into English and published as part of “Churchill’s Collection of Voyages and Travels” of 1704 as “A Curious and Exact Account of a Voyage to the Congo in the years 1666 and 1667.”

In the same volume was the work of another Capuchin, Father Jerome Merolla da Sorrento entitled “A Voyage to Congo, and several other countries chiefly in Southern-Africk, in the year 1682.”

However it was on the other side of the continent, in Ethiopia that the majority of the intellectual effort was lavished. Following on from Alvares, much work was done by Jesuit missionaries who were there between 1557 and 1634. The Jesuit Manoel de Almeida wrote his “Historia da Etiopia” making great use of the unpublished writing of another Jesuit, Pero Paez. However this was for long only know in Balthasar Telles’s abridged version “Historia geral de Ethiopia a Alta” published in Coimbra in 1660. An English edition was published in London in 1710 entitled “The Travels of the Jesuits in Ethiopia.”

Another Jesuit whose work Telles made use of was Jerome Lobo, who was a companion of the last Latin Patriarch, Alphonse Mendez. His “Historia de Etiopia” was supposedly first published in Coimbra in 1659. Several translations followed and interestingly the first complete English translation was Samuel Johnson’s first prose work published as “A Voyage to Abyssinia by Father Jerome Lobo” at London in 1735.

In 1634 due to their high-handedness and their attempted suppression of the Abyssinian church the Portuguese and the Jesuits were ignominiously expelled from Ethiopia, or those that didn’t loose their heads on the way.

This quarto edition was unfortunately not as lavish as the first edition with the magnificent plates severely reduced in size